The EU and China Between Competition and Cooperation: Political and Industry-Specific Challenges

Author: Marco Zecchillo, Head Researcher G.E.O. – Economics

Abstract

European Union – People’s Republic of China history of relations has undergone several phases of cooperation and competition, at alternate times, throughout numerous policy areas. Since the initial steps of a complex partnership, which occurred in 1975 (the year in which formal relations were initiated), the European Union’s approach to China has changed, as can be appreciated by European Commission’s Communications of recent years. The 2019 Joint Communication, entitled EU – China – A strategic Outlook, and the EU – China 2020 Strategic Agenda for Cooperation, and further official European Commission sources will be employed within this analysis in order to shed light on the kaleidoscope characterising this relation. The two economies are, under all terms, of enormous relevance for the sustainability and soundness of the global market. The PRC, via its astonishing rise, has been able to run constant and sustained Gross Domestic Product growth above 6% since 1990, with 2020 being an exception (World Bank, 2021). It consists, in the World Bank’s words, of the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history (World Bank, 2017). In this respect, Chinese businesses and investments have seen widespread growth, making them relevant for receiving economies in Europe, raising the stakes for the EU’s long – term economic policies. In particular, the analysis will hinge upon several sectors which the European Union deems to be extremely relevant, as important attachments to its trade policies, due to their relevant potential impact on society. Under this light, seeking cooperation with China is expected to increase overall global payoff, maximising the reach of initiatives that are dear to the Union. Some of them relate to the Environment, whose fundamental character is being increasingly recognised by EU policymakers for its existential component (epitomised, amongst others, by the considerable share of NextGenEU Recovery Plan financing earmarked for the support of green projects), threatening the very sustainability of human life and its prospects for growth. Furthermore, two other sectors that are clearly intertwined amongst each other, and to the latter aspect, are Technology and Digitalisation. These three issue areas are touched upon paragraph 3 of the EU – China 2020 Strategic Agenda. The paper will deal with the general standing of the European Union on these issues and the arguments it fosters. Additionally, a literature based review of historical and potential areas of cooperation, together with the respective obstacles, might be useful to trace possible future developments, in a provisional fashion. Nevertheless, instances of confrontation have erupted, exemplified by the freezing of negotiations of the CAI. These aspects impose a revision of the main divergences that make actual cooperation materially less feasible on the previously announced arrangements.

The new EU – backed initiative, the Global Gateway, and its attention to the environment, technology and digitalisation, could be instrumental in grasping the evolving EU stance on these relevant issues and in unpacking the direction the relation with PR China (with its Made in China 2025 initiative) may follow in the medium term.

EU – China Critical Aspects on Potential Cooperation: Environment, Technology and Digitalisation

These three areas, at the core of European Union’s pushes for modernisation, strongly interact with each other. In this context, a fully-fledged partnership with China entails potentially mutual benefits, but political implications arise upon these issues.

Across its official documents, it is possible to notice a certain degree of consistency in EU policy communications. As a matter of fact, the three pillars already present inside President Von der Leyen’s Political Guidelines (i.e., Environment, Social and Digital instances) appear to be ubiquitous and, on paper, intertwined to be mutually reinforcing. The Commission Communication EU-China: A Strategic Outlook underscores a European awareness of the weight the relation with China possesses, also in the light of its multi-decennial history. However, the interaction between these two players has grown in complexity, now calling for a shift towards a more “multi-faceted approach” (European Commission, 2019). EU’s selective engagement with the Asian partner is garnered from the famous catchphrase, visible at page 4 of the aforementioned publication:

"China is, simultaneously, in different policy areas, a cooperation partner with whom the EU has closely aligned objectives, a negotiating partner with whom the EU needs to find a balance of interests, an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership and a systemic rival, promoting alternative systems of governance"

The Strategic Agenda restates the last ideas, acknowledging the necessity of coordination and cooperation in key domains, amongst which it is possible to appreciate the presence of the Environment and Communication Technology. Within Paragraph 3, Science, Technology and Innovation, a reinforcement of science, technology and innovation, […], as to tackle common challenges […] and deliver win-win results is seen as desirable on the side of the Union. These lenses allow for a deeper interpretation of why Sino-European relations appear ambiguous. In many domains cherished by the European Union, a non-differentiated approach to Beijing may negatively affect its own interest, due to important security or geo-economic issue linkages. In the following paragraphs the feasibility of the previous remarks will be discussed, focusing on environmental and digital innovation issues.

2. Environment in EU – China Relations

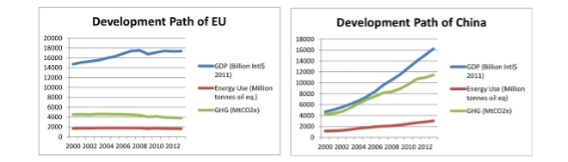

China is, at the time of writing, the largest producer of greenhouse gases. Carbon Dioxide emissions have risen quite sharply, in the Asian country, from 2001 to 2012, passing from 3.51 to 9.78 billion tonnes (Global Carbon Project, 2021). Nevertheless, the trend appears to have begun an early phase of peaking since 2013, with a declining second derivative. Overall, the PRC provides 28 percent of the global greenhouse gas emissions. On the contrary, the EU production of CO2 appears to have been in a declining trend for the last decade, after a prolonged peak and timid descent between the 1970s and the early 2000s (Tiseo, 2021). Certainly, the Union and China currently find themselves at different historical moments of development. In the former, the growth rate of the economy has shrunk, driven by a declining output (with respect to 2007) in Italy and Spain (World Bank, 2022). China, albeit beginning to signal declining rates of growth since the late 2000s, is still increasing its size by over or close to 6% each year, 2020 excluded.

Figure 1: Different Momenta in Economic Trends (2000-2012). Source: Liu et alia, 2019.

The latter point may hamper the prospect for a short-term overall cooperative outcome, also in the context of Xi Jinping’s 2020 announcement, in which the President pledged to drive the country into reaching peak emissions before 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060 (Herrero et alia, 2021). In this respect, the PRC appears to have engaged in a long-term path to the attainment of the objective, but still lacking the commitment of the European Union (symptomatic of this, in addition to the previously announced attention in the NextGenEU funds erogation, are Ursula Von Der Leyen’s Political Guidelines: A Union That Strives For More and the inclusion of the Green Deal as the First Pillar). The EU enjoys a particularly favourable perception at the external level, which it may employ to shape international consensus of swifter environmental regulations. The 2017 departure of the United States from the Paris Agreement, albeit temporary and immediately reversed by President Joseph Biden on his first day in office, January 20 2021 (Department of State, 2021), could have offered the EU and China the opportunity to produce meaningful impact in climate policy. As we have seen, a sufficient level of legislation and institutionalisation of a cooperative regime appeared to be lacking, due to the cautionary attitude of the EU in engaging politically with China and the specular rejection of legal structures originating in Europe purported by Beijing (Liu, 2019). Beijing appears, in all ways, to be interested in attaining increased reputational power worldwide, seemingly by supporting existing regimes and by developing new undertakings, such as the Belt and Road Initiative. Environment-related issues could represent a market in which the Asian power may play the role, in Robert Zoellick’s words, of a responsible stakeholder.

One of the pivotal side–markets in climate policy is embodied by the positive climate effect linked to an increasing utilisation of renewable energies, to limit the harmful outcomes of coal and petrol in the environment. As maintained by Sattich, one case for potential cooperation revolves around renewable energy, as a hypothetical provider of incentives for mutually beneficial cooperation, with expected collaboration in R&D and technological advancement (Sattich, 2017). Already, China has aimed throughout the years at improving its technological position in global markets, now accounting for 20 percent of overall world R&D expenditure in 2017, with a projected trend of growth (European Commission, 2017). Although a EU - China shared strategy for upgrading the technological fabric could be impactful, it would entail parties negotiating to have their standards gain the primacy, to maintain competitiveness and lower the cost of adjustment (Gabriel, 2017). Reasonably, a political power meaning could be attached by European and Chinese counterparts, discounting the benefits for the establishment of an international regime. In Oertel, Tollmann and Tsang’s perception, Euro – Chinese dealings on the matter will be characterised by a mixed outlook of cooperation and competition (Oertel et alia, 2020). The main idea is that the latter, if well managed by an established institutional framework, could, in the end, turn into what game theorists would name “Coopetition”, triggering a “race to the top” of innovation. At the same time, the EU shall pay attention not to lower its standards and keep clear and identifiable requirements for the acceptability of inbound and outbound investment in environmentally sensitive areas. Otherwise, unrestrained rivalry may unfold to be disruptive of technological advancement in this sector, lowering the payoff of the parties, even when considered singularly.

3. Tech and Digitalisation: European and Chinese Positions

The importance of technology in defining future economic relations, as was exemplified by the previous concepts, imposes a broadening of the picture to include a breakthrough sector in international markets and relations: digitalisation.

In the realm of digital technology, the European Union appears to stand aside in the advancement race between the USA and China, with the EU market being a ground of competition between these two tech superpowers. According to the European Investment Bank, 66 percent of the Union’s enterprises have reported having installed at least one digital technology, with a wide variance in observations across Member States. In the United States, conversely, the share was found to be almost 80 percent (EIB, 2019).

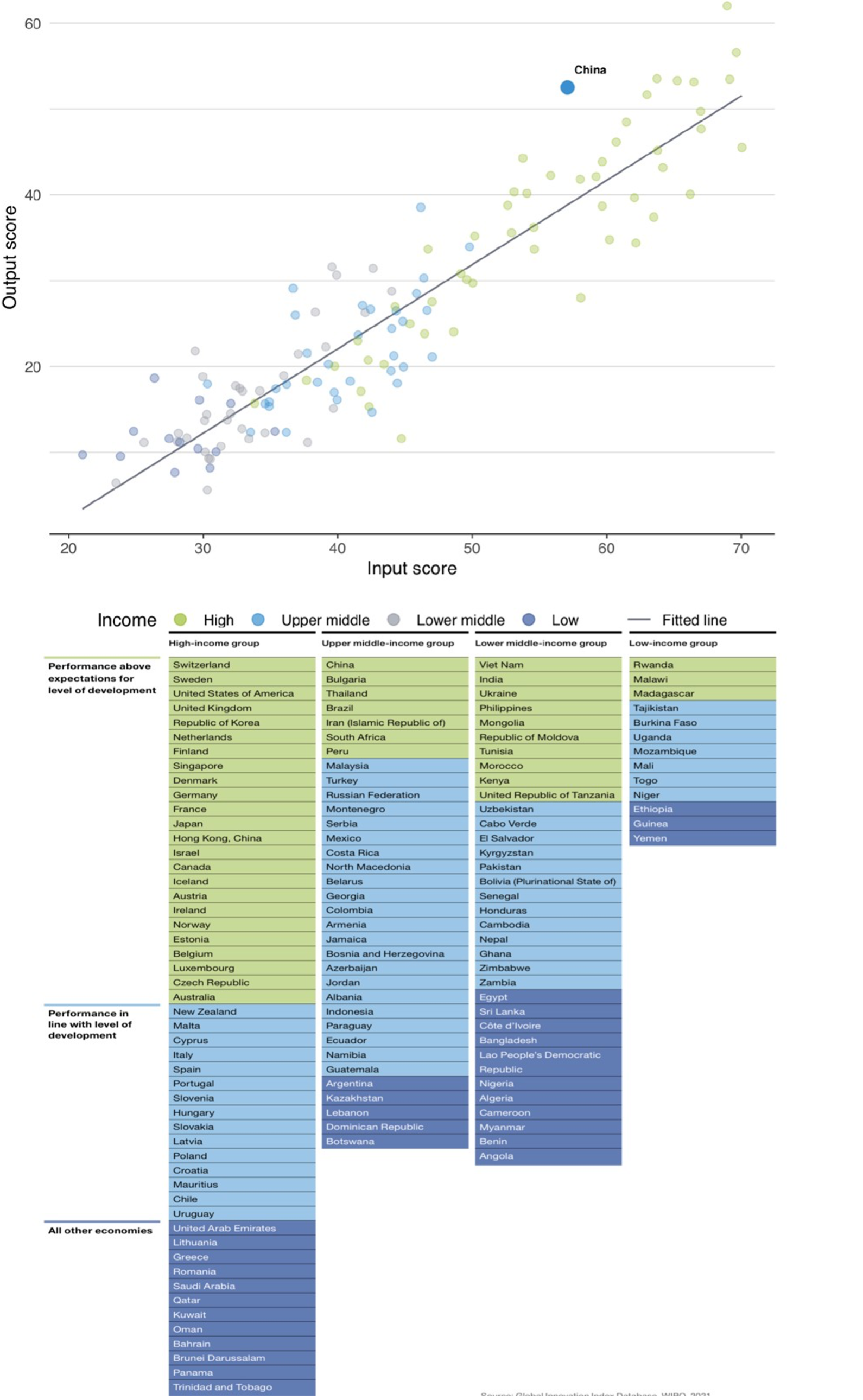

The EU may possess, therefore, a smaller global negotiating leverage and could play less as a trend- setter as far as digital standards are concerned, despite incorporating some of the most innovative economies in the world, according to the WIPO Global Innovation Index (WIPO, 2021a). The latter paper may be useful in providing a framework to understand the relative position of European countries with respect to China in the Tech innovation domain.

According to the World Intellectual Property Organisation, China’s Global Innovation Index (a pooled indicator grouping 80 determinants of innovation, to capture the multi-dimensional outlook of the latter phenomenon) was ranked 12th worldwide, while the country was placed 25th in Innovation Inputs (Human Capital, institutional, infrastructural and business sophistication R&D). The highest ranking is attained in Knowledge and Technology (K&T) outputs (4th place worldwide), while relatively less innovation is seen in the institutional environment (61st place) (WIPO, 2021b). Albeit not sitting at the very top tier, Beijing displays an above-average performance in translating input into output innovation, as can be appreciated by the graph hereby provided (figure 2) and by Figure 3 (in terms of an above-expectation performance considering the level of development, proxied by per capita income). Possibly, as can be grasped from the graph, the high rank of China is substantially supplemented by its staggering result in K&T input-to-output translation, while almost all EU countries appear at inferior ranks (except for Sweden, which places second worldwide).

Figure 2: China’s above average performance in input to output translation. Source: WIPO, 2021

Figure 3: Many EU Countries underscore innovation levels that are higher than what one would expect, considering their level of development. Source: WIPO, 2021.

Similarly, many EU countries sit in the high – income group and show performances higher than expectations (WIPO, 2021c), such as Sweden, The Netherlands, and Finland, amongst many others. Given these premises, many commentators expect the renovated boost towards a smarter China undertaken by the country’s leadership to contribute to the creation of a window of opportunity for international, and, therefore, EU enterprises’ investment (Alves Dias et alia, 2019; Wubbeke et alia, 2016). In this respect, a cooperative outcome, producing benefits for both parties (industrial upgrading in China and profits for European outward-investing firms), may materialise. The augmented demand in the People’s Republic may induce European firms with a high level of know-how and sectoral expertise to channel FDI towards the country, provided that China currently may lack the technological level to reach the set goal of industrial upgrading, therefore requiring substantial investment.

As a matter of fact, despite the sheer size of its digital market, the sector’s value added on the total economy (5.6% in 2016) is showing noticeable growth rates, but it is still not bigger than the OECD average (Herrero et Xu, 2018a). This reinforces the assumption that the Chinese market may still be demanding know-how to turn inputs into outputs. The former could possibly still be low due to intense export of technology such as computers and smartphones, which are assembled in China and sent abroad, to produce value added elsewhere (Herrero et Xu, 2018b). Nevertheless, the Chinese ICT domain disclosed 1.8 times greater labour productivity with respect to the indicator’s average in the country, with a 10 percent value added growth rate between 2013 and 2016, outperforming the declining trend of output growth (Bruegel, 2018).

On the other side of Eurasia, EU firms may be presented with a wider market, with feasible and profitable opportunities of investment awaiting, provided the considerable potential expansion the Chinese ICT economy may have. Despite a potential opening of mutually beneficial exchanges, several structural constraints set some hurdles to EU businesses’ operations in the PRC, such as joint venture requirements (through which Chinese investors would always possess the upper hand in resource contributions for establishing new business projects) and difficulties in gaining public procurement (for instance, a mandatory qualification certificate under Special Qualification Requirements is to be presented by foreign companies. De facto, foreign-invested firms are expected to establish Chinese subsidiaries in order to qualify) (Burkhardt, 2018). Moreover, the missed attainment of the CAI has contributed in disrupting investors’ faith to operate in the Asian market with more flexibility. Reaching the objectives laid down in the previously described policy documents, in the realm of improving cooperation on innovation, may be possible due to the presence of potential mutual benefits. Nevertheless, practical hurdles require adjustments to install a synergic convergence of market access requirements and reciprocity, which is currently lacking amidst the freezing of the CAI (Comprehensive Agreement on Investment) negotiations (Kratz, 2021; European Commission, 2020). In dealing with China in the technological domain, these instances will need to be taken into consideration, as to avoid asymmetric interdependencies with Beijing, across Member States. Asymmetries and different magnitudes of interdependence on China may provoke diverging degrees of risk and uneven vulnerabilities across union countries (China Monitor, 2020).

Potential EU-China Competition: Global Gateway vs MiC2025

The Global Gateway (GG) arises as part of a reignited EU international stance to emerge as an all- round superpower of the 21st century, focusing on smart, clean and secure links for digital, energy and transport (European Commission, 2022a). Amidst the EU – China competitive dialectic, the GG may appear as an instance of Europe’s willingness to enhance its position vis à vis the Chinese initiatives under the Belt and Road and Made in China 2025 projects. Several sources report the EU – backed undertaking as a potential counterbalance or an alternative to China’s BRI, provided the similar rationale shared by the two policies: that of updating infrastructure across the Eurasian and African macro region (Dinis, 2022; Kliem, 2021; Brinza, 2021; Gerstl, 2021).

4. Global Gateway: Rationale, Funding and Innovations

The Global Gateway, being a strategy officialised by Ursula Von der Leyen’s Commission, follows the path already traced by the early formulation of the Political Guidelines (the paper of reference is A Union that Strives for More: My Agenda for Europe by then-candidate to the presidency Von der Leyen). In this context, the five thematic pillars of the Gateway (namely, Digital Sector, Climate, Transport, Health and Education) are certainly intertwined with those of the Guidelines (i.e., European Green Deal, Social Rights – which contains a paragraph devoted to Empowering People Through Education and Skills, and the strife for Digitalisation). The EU strategy aims at being delivered via funding risen from a synergy of Member States, private investment and EU – level financial and development institutions for additional resources (European Commission, 2022b). The bulk of funding is expected to be found within the 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework. More specifically, the heading named Neighbourhood and the World is expected to provide substantial support to the Gateway, through the NDICI (Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument). Nevertheless, the heading’s magnitude remains substantially lower than the projected spending for the new strategy, which was defined to be EUR 300 Million to be invested by 2027 (European Commission, 2022c). The latter budget section is expected to be endowed with EUR 110.6 billion, and no additional allocation is awaited as a share of the 750 billion of the Next Generation EU (European Commission, 2021).

Despite these constraints, the Commission argues it can raise up to 135 billion from the European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus (EFSD+), 18 billion in grants from the budget and 145 billion from financial and development finance institutions. An institutional innovation may reveal itself to be the setting of a European Export Credit Facility, to support the current export credit mechanisms that are already present within member states. This is possibly aimed at creating a background of certainty for SMEs to accede extra-EU markets with enhanced easiness (European Commission, 2022d).

5. Global Gateway: An Alternative to China’s MiC25?

China’s strategy has an inherently different underlying rationale, if compared to the EU policy. The Global Gateway possesses an outwards-looking character, given the interest and the attention paid to Neighbourhood. Moreover, the financial magnitudes of the two policies are broadly different: the MiC is estimated to be funded with at least 1.4 trillion dollars (to be spent within the 2021-25 Five Year Plan). Nevertheless, some points of fracture, exacerbating competition, may arise.

MiC could, instead, end up being aimed at the self-strengthening of the largest consumer market in the world (Wubbeke et alia, 2016; Amighini, 2018) towards the attainment of the Made in China ideal. The latter encompasses the upgrading of the country’s manufacturing structure via enhanced smartness and digitalisation. As previously discussed, the latter aspect may exacerbate fresh European investment flowing into the Asian country, given an increased demand for high-level know-how and devices. However, a renovated and strengthened internal Chinese market in the technological domains could produce effects on the country’s standing in external political and economic relations.

As previously announced, substantial cleavages remain in EU-China relations, that may pave the way for incompatibility of means and objectives, and, therefore, competition. It is reasonable to hypothesise structural constraints on both sides. Provided the presence of differentiated treatments for investments, these flows are unlikely to materliase in the absence of an equitable level playing field and reciprocity. Moreover, the conditionalities the European Union attaches to its global strategies (as environmental or social standards, whose presence appears to be constant throughout EU’s) do not increase the likelihood of a positive Chinese response, curbing the prospect of a fully-fledged cooperation, at least in the short term.

Particularly, an area within which a competitive outcome may prevail is the African continent, historically tied both to Europe (plus the United States) and to the People’s Republic. In this respect, the EU initiative in the continent arises as the outcome of a process of rethinking of the digital strategy it needs to entertain with its southern partners (Teevan, 2021). In the 2021 paper entitled A New EU-Africa Strategy, which predates the Global Gateway formulation, digital transformation appears as the second pillar of the potential new synergy between the two continents (EPRS, 2021).

In this context, the People’s Republic of China has not been shy in increasing its investment in Africa, under the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). The stated goals of strengthening companies (the “Champions”) operating in the so-called “key industries” (Mc Kinsey, 2015) could further lead to increasing competition. Many of them, such as Huawai and Zhongxing Telecommunications Equipments (ZTE), which were central in recent years in upgrading the African digital infrastructure, may have the upper hand in this market, due to their already established position and their close ties to the central Chinese government (Arcesati, 2021), which could render them more competitive vis à vis European or Western counterparts (Galchu, 2016). Some of these enterprises, such as Huawei, have been at the centre of discussion and mistrust in Europe, in addition to Court judgements (such as that of 2015 against Huawei and ZTE on the observance of competition rules under article 102TFEU), which could be symptomatic of an intricate and challenging future path for possible cooperation.

Possibly more importantly, the looser conditionalities of Chinese investments are, in this scenario, a factor that could tilt the balance in favour of China in the African area, against EU’s pushes towards the observance of environmental and social standards when providing funds (EPRS, 2021b).These conflicting stances signal that competition may prevail, at least in the realm foreign initiatives of the two parties.

Concluding Remarks

China and the European Union could, potentially, begin deep cooperation in a wide array of sectors. Some of them, such as those treated within the analysis, are particularly salient, given the possible impacts on the welfare of Union citizens. This aspect has made policymakers, the Commission in primis, define a differentiated strategy for the European engagement with the PRC. What could the future have in store for the relation? Given the multiple variables at play, it is challenging to pinpoint a single takeaway. The theoretical understanding proposed by Gowa and Mansfield, two important International Political Economy scholars, may shed light on the overall payoffs of the European Union- China relation. According to them, the positive benefit of entertaining an cooperative relation with another state is discounted on a Security Externality, that can either reduce or enhance the overall satisfaction level of the contracting party. In the case of China, the discounts are likely to be negative in several sectors with important security implications, and to be different on a country-to-country basis. The challenge for this relation is whether these discounts, which rely on risk perception of both parties, could be overcome to produce an overall benefit for the world, given the magnitude of the two actors.

China and Europe could collaborate in the previously analysed issue areas, but structural constraints as market access or standards would still exist. However, in order to amplify the environmental and sound digitalisation policy impact, cooperation is surely needed. One possible scenario may see the EU accepting compromises on standards, while another hypothesis is that of China assuming an enhanced stakeholder role in the global economy. This is, as a matter of fact, likely to materialise in the medium to long run, provided the recent Chinese commitments, exemplified by its stance on reaching peak emissions and later reducing them, even though the environmental question demands for immediate planning, as the EU understands.

On the contrary, having the European Union stressing elevated standards in these domains may itself be dismissive towards deeper EU-China integration, given China’s reluctance to accept European standards, as previously underscored. Surely, to conclude, the EU would gain if it becomes better able at conveying an organic and unitary voice in the relation. Multiple and differentiated views of relatively small member states (with respect to China) risk to reduce overall negotiating leverage, materialising exactly what the EC creation aimed at avoiding (i.e., a divided Europe), back in the 1950s.

Sources

Alves Dias P., et alia (2019). China: Challenges and Prospects from an Industrial and Innovation Powerhouse. European Commission Publication Office, 2019. (A-2)

Amighini A. (2018). What the MiC 2025 Means for the Chinese Economy. ISPI Commentary, August 2018. Available at: www.ISPI.it/it/pubblicazione/what-mic-2025-means-Chinese-economy-21108(B-1)

Arcesati R. (2018). Chinas Evolving Role in Africa’s Digitalisation: From Building Infrastructure to Shaping Ecosystems. ISPI Commentary, 2021. Available at: www.ispionline.it/en/pubblicazione/chinas-evolving- role-africas-digitalisation-building-infrastructure-shaping-ecosystems-31247 (B-1)

Brinza A. (2021). The Global Gateway Joins the Competition Against the BRI. China Observers, 2021. Available at: www.Chinaobservers.eu/the-global-gateway-joins-the-competition-against-the-BRI/(B-1)

Beiten Burkhardt (2018). China: Public Procurement: Opportunities and Challenges. Paper No. 11/2018, Beiten Burkhardt, 2018. (C-1)

European Commission (2022). International Partnerships: China. European Commission, 2022. Available at: www.ec.Europa.eu/international-partnerships/where-we-work/China_en (A-1)

European Commission (2022). China’s Restrictions on FDI are Much stronger in the EU and US. EU Science Hub, 2022. Available at: www.joint-research-centre.ec.Europa.eu/crosscutting- activities/facts4eufuture-series-reports-future-Europe/china-challenges-and-prospects-industrial-and- innovation-powerhous/chinas-restrictions-FDI-are-much-stronger-eu-and-us_en (A-2)

European Commission (2022). Global Gateway. European Commission, 2022. Available at: www.Europa.eu/info/strategy/priorities-2019-2024/stronger-europe-world/global-gateway_en (A-1)

European Commission (2021). Make it Green. European Commmission, 2021. Available at: www.Europa.eu/next-generation-eu/make-it-green_en (A-1)

European Commission (2021). Headings: Spending Categories. European Commission, 2021. Available at: www.ec.Europa.eu/info/strategy/eu-budget/long-term-eu-budget/2021-2027/spending/headings_en (A-1)

European Commission (2020). Eu Trade Relations with China: Facts, Figures and Latest Developments. European Commission, 2020. Available at: www.policy.trade.ec.Europa.eu/eu-trade-relationships- country-and-regions/countries-and-regions/china_en (A-1)

European Commission (2019). EU-China: A Strategic Outlook. European Commission, 2019. Available at: www.ec.Europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/communication-eu-china-a-strategic-outlook.pdf (A-2)

European Commission (2017). China’s R&D Strategy. Competence Centre on Foresight, 2017. Available at: www.knowledge4policy.ec.Europa.eu/foresight/topic/expanding-influence-east-south/industry- science-innovation_en (A-2)

European External Action Service (2013). EU – China 2020 Strategic Agenda For Cooperation. EEAS, 2013. Available at: www.eeas.Europa.eu/archives/docs/china/docs/eu-china_2020_strategic_agenda_en.pdf (A-1)

European Investment Bank (2019). Who is Prepared for the New Digital Age? EIB, 2019. Available at: www.eib.org/en/publications-research/economics/surveys-data(eibis-digitalisation-report.htm(A-1)

EPRS (2021). A New EU-Africa Strategy: A Partnership for Sustainable and Inclusive Development. European Parliament, 2021. (A-2)

Gabriel J., Schmelcher A. (2017). Three Scenarios for EU-China Relations 2025. Elsevier, 2017. (B-1)

Galchu J. (2016). The Beijing Consensus versus the Washington Consensus. African Journal of Political Science and International Relations Vol. 12, January 2018. Pp. 1-9. (B-2)

Gerstl A. (2021). Can EU’s Global Gateway Compete with China’s BRI?. Central European Institute on Asian Studies, 2021. Available at: www.ceias.eu/ceias-considers-can-eus-global-gateway-compete-with- chinas-BRI/

(B-1)

Herrero A., Tagliapietra S. (2021). China has a Grand Carbon Neutrality Target but Where is The Plan.

Bruegel, 2021. (B-1)

Herrero A., Xu J. (2018). How Big is China’s Digital Economy?. Bruegel Working Paper, Issue No.4, May, 2018. (B-2)

Kliem F. (2021). Europes Global Gateway: Complementing or Competing the BRI. The Diplomat, 2021. (B-1)

Kratz A., Oertel J. (2021). Home Advantage: How China’s Protected Market Thretens Europe’s Economic Power. ECFR, 2021. Available at: www.ECFR.eu/publication/home-advantage-how-chinas-protected- market-threatens-europes-economic-power/ (B-2)

Liu L., Wu T. Wan Z. (2019). The EU China Relationship in a New Era of Global Climate Governance. Asia- Europe Journal No. 17, 2019. Pp. 243-254. (B-2)

McKinsey and Company (2015). China is Betting Big on these 10 Industries. McKinsey, 2015. Available at: www.web.archive.org/web/20180915122827/ (A-2)

Oertel J., Tollman J., Tsang B. (2020). Climate Superpowers: How the EU and China can Compete and Cooperate for a Green Future. ECFR, 2020. Available at: www.ecfr.eu/publications/climate-superpowers- how-the-eu-and-china-can-compete-and-cooperate-for-a-green-future/ (A-2)

Sattich T. (2021). Renewable Energy in EU China Relation: Policy Interdependence and its Geopolitical Implications. Elsevier, 2021. (B-1)

Teevan C. (2021). Building Strategic Digital Cooperation with Africa. ECDPM Briefing Note No.134, 2012. (B-2)

Tiseo I. (2021). Carbon Dioxide Emissions in the European Union, 1965-2020. Statista, 2021. Available at: www.statista.com/statistics/450017/co2-emissions-europe-eurasia (A-1)

US Department of State (2021). The US Officially Rejoins the Paris Agreement. Department of State Press Statement, 2021. Available at: www.state.gov/the-united-states-officially-rejoins-the-paris-agreement/ (A-1)

World Bank (2022). GDP Growth (Annual %) – European Union. Available at: www.data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=EU(A-1)

World Bank (2021). GDP Growth (Annual %) – China. Available at: www.data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=CN(A-1)

World Bank (2017). China Overview. World Bank, 2017. Available at: www.worldbank.org/en/country/chinaoverview(A-1)

World Intellectual Property Organisation (2021). Global Innovation Index. WIPO, 2021, pp. 3-5; p.24; p.30, p.67. (A-1)

Wubbeke J., Messner M., Zenglein M. (2016). Made in China 2025: The Making of a High Tech Superpower and Consequences for Industrial Countries. MERICS, 2016. Available at: www.merics.org/en/report/made- china-2025

(B-1).